Blood and guts - a community at war

At Englesea Brook Chapel & Museum of Primitive Methodism, Britain's involvement in the First World War continues to be commemorated with an exhibition focusing on conscientious objection: "Blood and guts - a community at war" by Professor Michael Hughes. Dr Jill Barber, vice president of the Methodist Conference and project director at Englesea Brook Museum, asks: Whose voices are being heard? Have we, as Methodists, a distinctive contribution to make to the debate about peace and war, which is just as urgent today?

In August 1914, the Primitive Methodist Leader thundered, "A wave of madness has swept over Europe, and Britain is invited to plunge into a fury that is insane."

A week later, in an astonishing U-turn, Primitive Methodist President Arthur Guttery called for young men to enlist, declaring, "Our chapels are not the refuge of dissent; they are the citadels of liberty, and they train men who will break all tyranny in pieces." Methodist women were not exempt: "Braver still are the women, who surrender their husbands, sons and sweethearts, and who hide their tears in smiles that their loved ones may not be distressed."

Many responded to the call, believing - as did Wesleyan President Dinsdale Young - that "love of country is part of the love of God". But others, also for conscience's sake, chose a path that led to rejection, persecution and, in extreme cases, death.

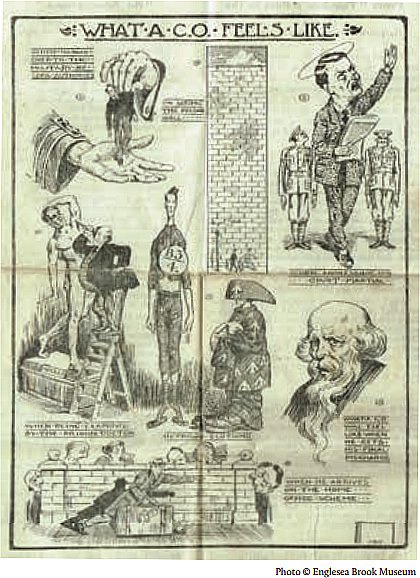

There were 16,000 conscientious objectors (COs) during the First World War. Many were Quakers, but they also included Plymouth Brethren and Christadelphians, whose churches all took an anti-war stand. For Methodists, and other non-conformists, it was much more difficult.

The chairman of a military tribunal examining men whose beliefs would not allow them to fight declared: "Men who are not Quakers … are really not conscientious objectors". One Wesleyan CO was told that he could not be granted exemption because it was "not part of the creed of the Wesleyans that fighting is a wicked thing".

No wonder that ordinary Methodists were confused by the alliance of their church with the state. Methodism had taken a peaceful stance throughout the nineteenth century, but now Christians who felt it was contrary to the gospel to take up arms were called 'cowards' and 'shirkers'.

It was not a decision made lightly. While not doubting the courage of those who enlisted, one young man believed those who refused to kill "are heroes just as great". Another admitted that "at heart he was a conscientious objector, but was too much of a coward to face its consequences"

For more stories of Methodists, including on William Done, and James Foister, imprisoned with Bert Brocklesby featured in the commemoration worship on 20 March, see Brave enough to say no and the story of Jack Foister, one of the '35 Frenchmen'